This is a blog post that I wrote some months ago, but never got around to getting past the draft stage. While it is late, it is certainly better than never posting it at all. My only hope is that someone might draw some hope and encouragement from my own story.

This is a blog post that I wrote some months ago, but never got around to getting past the draft stage. While it is late, it is certainly better than never posting it at all. My only hope is that someone might draw some hope and encouragement from my own story.

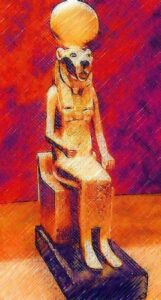

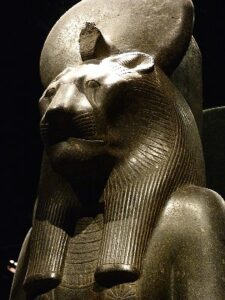

There comes a time in every healer’s life when we have to face challenges for our own health. While this is not something that I tend to discuss publicly on social media very much, it is something that I thought was important to discuss in relation to my work with Sekhmet as Her Priestess. Facing a health challenge or crisis should never be seen as a “failure”. Even though some part of us, something within us will want to lay blame or say, “Well, if you were worth a damn as a healer, as a priestess, or whatever, you wouldn’t be going through this now!”

That notion is wholly and blatantly false. While life expectancies have certainly increased over time, we are now living in a toxic stew to the degree that we are now facing another mass extinction on the planet. There are plenty of things out there to be paranoid about, lots of ways we really need to pay attention because there are those people and corporations who don’t give one bloody damn about the rest of us. The result is and has been more people – both children and adults suffering from a wide range of chronic diseases or illnesses that range from asthma to various forms of cancer. It has gotten to the point that if you are someone who has no health issues whatsoever or an insurance company cannot say that you have “a pre-existing condition”, then you are a rare individual indeed. It should come as no surprise that the insurance companies and the politicians on one side of the aisle would like to eliminate protections for those of us with one or more of those conditions so that the investor class makes more in profits than they have to pay out in health care costs.

A little more than a decade and a half ago, my mother was diagnosed with breast cancer. At the time of her diagnosis, she didn’t or rather wouldn’t accept it. I personally believe that she wasted a lot of precious time by being in denial about the seriousness of what was going on. Nevermind that my maternal grandmother was also diagnosed with breast cancer and was able to beat it because they caught it very early and Grandma had an attitude to addressing things head-on. My mother, on the other hand, got stuck between the first in a set of choices that Susun Weed outlines in her book, “Breast Cancer? Breast Health!” which was to “do nothing” and the second choice, which is to “gather information.” My mother felt that if she both kept doing nothing and gathering as much information as possible, the reality of her disease would go away on its own.

Of course, it didn’t. In the fall of 2001, despite chemotherapy and radiation, she lost her battle with breast cancer after it had metastasized into her bones.

Now, almost a full 15 years after her passing, I found a lump in my own breast. I tried to make an appointment to get in as soon as possible with my physician as soon as I noticed it, but was put off by the scheduler as I had my regular physical coming up in four weeks. Fast forward through those four weeks to the actual appointment, I was asked why I didn’t come in sooner. I told my doctor that the receptionist had put me off. She was not pleased, to say the very least. For something like this, she told me, she would have made the time. Not once since her regular scheduler had been on vacation, had anyone been fit into her schedule. My doctor wanted me to go straight to radiology which was in the same medical complex and have a mammogram done immediately.

To make a long story less painful to read, the mammography, an ultrasound, a biopsy, and MRI showed was that I had what is called DCIS or Ductal Carcinoma in Situ. What it meant was that there were cells that were considered pre-cancerous and limited to one milk duct in my breast. The mass, however, was of considerable size and had been obscured by dense breast tissue, something that had been ongoing for me, and there was probably no way to just do a lumpectomy. I would probably end up losing at least my entire left breast.

The initial diagnosis, believe it or not, was the only time I allowed myself to cry about it. Why me? I have so much to do! That emotion probably lasted a few hours. Next, I was damned determined I was going to beat this thing. I was not going to be like the woman who gave birth to me. So what if I lost a breast? They could do reconstruction right then and there in the same surgery. Through the consultation processes, my doctors and I decided that because both my mother and grandmother had breast cancer, chances were I was probably someone who had a genetic mutation such as the BRCA gene that would put me at risk for other invasive cancers later in life much higher, that I would do a bilateral or double mastectomy with reconstruction.

I am happy to report that the final outcome was a good one. I got through breast cancer during the Covid-19 pandemic, and now, nearly five years later, I am cancer-free. I am grateful to the doctors and all who supported me in that journey, and especially for all the leaning that I had to do on the Netjeru, and Sekhmet in particular. She was always there for me. Even when I felt like I couldn’t make it through the process. During that journey, I met other women who were going through the same thing as I had. Some were older, and one, a very good friend, was going through the process in her mid-twenties! One thing that the experience and Sekhmet taught me was that even in adversity, we are all here to help each other as much as possible. We can be the vessel to bring the compassionate support each of us needs.

Depending on which day you celebrate the Helical Rising of Sirius – it is what we Kemetics note as Wep Ronpet, or our New Year. Admittedly, I have waited a couple of days to write this, not because I needed to recover from a wild bout of celebrations but to contemplate what I want this new year to be.

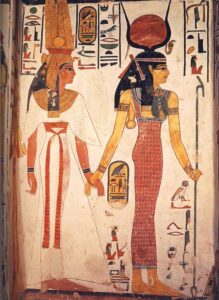

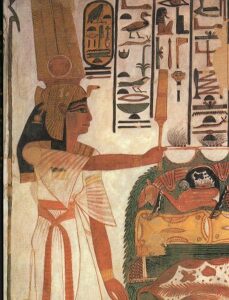

Depending on which day you celebrate the Helical Rising of Sirius – it is what we Kemetics note as Wep Ronpet, or our New Year. Admittedly, I have waited a couple of days to write this, not because I needed to recover from a wild bout of celebrations but to contemplate what I want this new year to be. We have now come to the last of the Epigomenal Days of Wep Ronpet and the celebration of the birth of the youngest child born of Nut and Geb – Nebt-Het or Nephthys . Her Name literally means ‘Lady of the House’, and She, like Her sister, Aset, is a Lady of Great Magic. Since about the Fifth Dynasty, Nebt-Het was called the Helpful Lady or Most Excellent Goddess. In some cosmologies, Nebtj-Het was paired with Set, while in others She was the wife of Yinepu (Anpu) or Anubis. Nebt-Het and Aset are perhaps best known for proceeding over funerary rite, such as when Wasir (Osiris) died and became the Lord of the Field of Reeds.. Because of this association, this Goddess is known to be of particular comfort to the deceased and those who survive them.

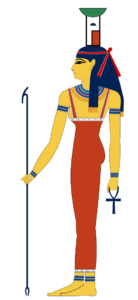

We have now come to the last of the Epigomenal Days of Wep Ronpet and the celebration of the birth of the youngest child born of Nut and Geb – Nebt-Het or Nephthys . Her Name literally means ‘Lady of the House’, and She, like Her sister, Aset, is a Lady of Great Magic. Since about the Fifth Dynasty, Nebt-Het was called the Helpful Lady or Most Excellent Goddess. In some cosmologies, Nebtj-Het was paired with Set, while in others She was the wife of Yinepu (Anpu) or Anubis. Nebt-Het and Aset are perhaps best known for proceeding over funerary rite, such as when Wasir (Osiris) died and became the Lord of the Field of Reeds.. Because of this association, this Goddess is known to be of particular comfort to the deceased and those who survive them. Today marks the day that we celebrate the birth of the Goddess Aset (Isis, Ast, or Iset). Of all the Egyptian gods and goddesses, Aset, the Mistress of Magic, or She of the 10,000 Names, is probably the best known throughout the world. Although Her worship began in ancient Egypt, it spread throughout the Greek and Roman world and traveled throughout the empire. Aspects of Aset’s worship can be seen even in Christianity.

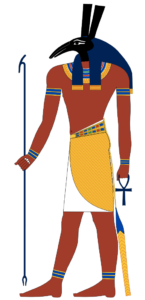

Today marks the day that we celebrate the birth of the Goddess Aset (Isis, Ast, or Iset). Of all the Egyptian gods and goddesses, Aset, the Mistress of Magic, or She of the 10,000 Names, is probably the best known throughout the world. Although Her worship began in ancient Egypt, it spread throughout the Greek and Roman world and traveled throughout the empire. Aspects of Aset’s worship can be seen even in Christianity. We have now entered the third Epigomenal Day of the Kemetic calendar leading up to Wep Ronpet, or Egyptian New Year. Also known as Seth or Sutekh, Set is the god of Storms and of the Red Lands or desert regions of Egypt.

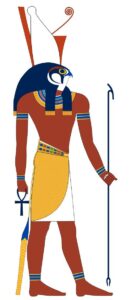

We have now entered the third Epigomenal Day of the Kemetic calendar leading up to Wep Ronpet, or Egyptian New Year. Also known as Seth or Sutekh, Set is the god of Storms and of the Red Lands or desert regions of Egypt. Today marks the Second Epagomenal Day in the Kemetic Calendar, the birthday of the Egyptian deity known as Heru-Wer,, Horus the Elder or Horus the Great. (Not to be confused with Heru Sa Aset, otherwise known as Horus the son of Isis, or Horus the younger.)

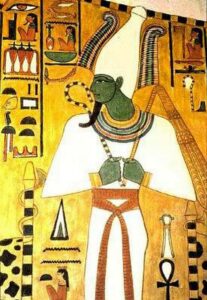

Today marks the Second Epagomenal Day in the Kemetic Calendar, the birthday of the Egyptian deity known as Heru-Wer,, Horus the Elder or Horus the Great. (Not to be confused with Heru Sa Aset, otherwise known as Horus the son of Isis, or Horus the younger.) We are now entering Wep Ronpet (Kemetic New Year) celebrations with the first of the epagomenal days. Today marks the first day leading up to what we Kemetics call Wep Ronpet or the Ancient Egyptian New Year. This is the day, according to the Egyptian faith, that is the birthday of the first of the Netjeru, Wasir, or Osiris.

We are now entering Wep Ronpet (Kemetic New Year) celebrations with the first of the epagomenal days. Today marks the first day leading up to what we Kemetics call Wep Ronpet or the Ancient Egyptian New Year. This is the day, according to the Egyptian faith, that is the birthday of the first of the Netjeru, Wasir, or Osiris. Once the cabinet and its frame were out of there, with the help of our friend Mark, we built the extension. It really is all about having the right materials and tools; we were able to do that portion of the renovation in about two hours. The results so far have been amazing.

Once the cabinet and its frame were out of there, with the help of our friend Mark, we built the extension. It really is all about having the right materials and tools; we were able to do that portion of the renovation in about two hours. The results so far have been amazing. For the kitchen counter, we needed not only a hammer and a chisel but also a heat gun to soften up the glue beneath the Formica. The kitchen counters took a couple of days to strip off entirely.

For the kitchen counter, we needed not only a hammer and a chisel but also a heat gun to soften up the glue beneath the Formica. The kitchen counters took a couple of days to strip off entirely. In the end, we went with a rounded 2″ x 4″ tile and put them in place. It still didn’t look quite right until we found some color-matched caulk and ran it along the upper edge of the backsplash and edging.

In the end, we went with a rounded 2″ x 4″ tile and put them in place. It still didn’t look quite right until we found some color-matched caulk and ran it along the upper edge of the backsplash and edging. The Table / Kitchen Island

The Table / Kitchen Island Thanks to the help of my dear friend and web developer, Shayne at CatchThis! I have moved my blog from WordPress dot com to a new place on the interwebs that lets me avoid the dreaded block editor that they have inflicted on everyone. If you don’t want to do the same, you can, of course, go back to the Classic editor that we all know and love for just $321 per year.

Thanks to the help of my dear friend and web developer, Shayne at CatchThis! I have moved my blog from WordPress dot com to a new place on the interwebs that lets me avoid the dreaded block editor that they have inflicted on everyone. If you don’t want to do the same, you can, of course, go back to the Classic editor that we all know and love for just $321 per year.